By: Aaron Clayton and Justin Tenorio

My partner and I had the honor of interviewing Dr. Benikia Kressler. Our interview was about an article she published titled “Learning Our Way through” Critical Professional Development for Social Justice in Teacher Education. During our interview, we not only got to see her results from the study she did involving faculty members. But also, how as an educator in one of the largest universities in the country, she noticed we teach in a culturally, experientially, and ideologically diverse context. And like her colleagues nationwide, they bear witness to the tensions and traumas associated with the current U.S. political climate.

Being an African American woman, she had dealt with suppression during her school years and wanted to contribute a way to help faculty better assist students who come from historically marginalized communities. Her goal was to raise awareness and serve to focus attention on the deficits of individual students or teachers as opposed to shining a spotlight on the systematic perpetuation and normalization of hegemonic structures built to uphold white supremacy by disenfranchising and marginalizing communities of color.

During our interview, Dr. Kressler said before earning her doctorate degree she worked in special ed and could tell there was a clear racial divide. Most of her students were male and Black or Latino. Then as she went on to teach in Miami Florida, she noticed that in her special ed classes, most of the students were Haitian or Cuban. When Dr. Kressler traveled to Atlanta she had the same problem most of the students were African American or Mexican male. Disproportionality in special education was another question that sparked interest. She wanted to help dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline as well as the misrepresentation of people of color in special education. Dr Kressler’s project was able to emerge from a university-sponsored and faculty development workshop that one of her colleagues at the time put together and led during the spring of 2016. After presenting a theoretical model for teaching about social justice and sharing examples from her undergraduate and graduate classes, she led attendees in brainstorming discipline-specific applications for them to utilize in their own classrooms. Her colleague later applied for and was able to receive an institutional mini-grant to support the development and delivery of a social justice-oriented CPD group, initially named the “faculty learning community” [FLC], during the 2017 18 academic year.

During that year Dr. Kressler conducted her research and was able to get 26 of her faculty members to volunteer and register for the FLC and complete at least one study-related instrument; of these 10 were “active participants” who attended all or most of the 11 meetings. Active participants represented six of the university’s nine colleges, including Communications, Education, Engineering, Health and Human Development, Humanities and Social Sciences, and Natural Sciences and Mathematics, and had between seven months and 25 years of service on the faculty. While the “Inactive” participants attended meetings and completed journals sporadically and generally indicated that their schedule prevented them from having full engagement. Women (90%) and people of color (60%) were overrepresented within the FLC as compared to the faculty, which at the time of her study was comprised of 51% women and 39% people of color.

Dr. Kressler speaks about critical processing which is to try and think about ways to dismantle oppression in areas such as white privilege and pushing against anti-blackness etc. Having a space at work for faculty members to be able to safely have those types of conversations was needed. During her research a question she asked on the registration form was what drew them to the FLC; About 35% of the open-ended responses referred to wanting a better professional community. Participants also described the need for a “support system” and a “supportive community,”.

Participants also referenced a desire to engage in collaborative scholarship, and a hope of finding allies as they sought to implement institutional change within their respective colleges at the university. Several participants noted specific incidents that had troubled them as their primary motivator, including conflicts with students or colleagues, while others spoke more generally about institutional factors that trouble their efforts to enact social justice on campus (“feeling as though we’re on a tightrope”) when attempting to teach about social justice on their campus.

For Dr. Kressler and her team to keep her same approach to their study they engaged in preliminary analysis during the FLC itself. And then several times

throughout the year, participants read, analyzed as well as coded anonymized data

from surveys and research journals, including questions related to their goals as

social justice educators, and then the interpersonal and institutional factors that help or was potentially hinder their efforts to teach for social justice. Throughout this process, one of her teammates documented the ways participants were categorizing and organizing data; they would later end up using her notes to triangulate data and ensure their analysis reflected participants’ own meaning-making processes.

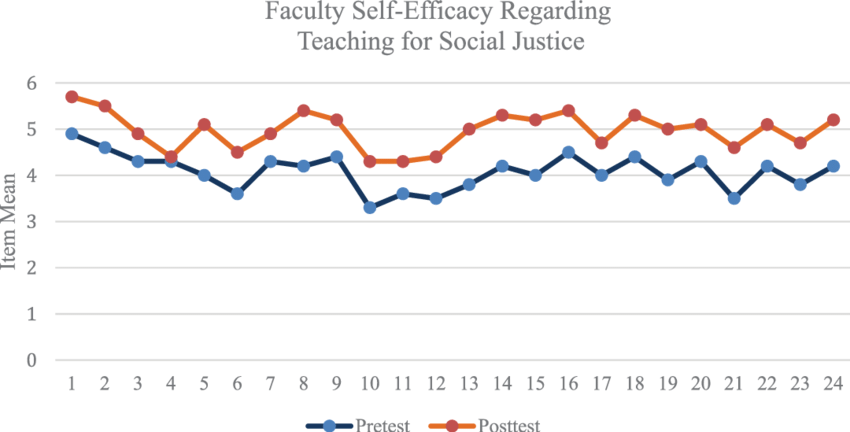

What she found at the end of her research was the depth of participants’ sense of disorientation within academia, as well as their collective hunger for community, professional learning, and strategic alliances when navigating inhospitable institutional conditions. They found that when participating in CPD (community professional development) their needs were met. As well as an increase in members sense of efficacy and authenticity as social justice educators.

Dr. Kressler interview was not only eye-opening but very educational as well. Her article was a good indicator of how not just educators but we as a society should try critical processing. Social justice isn’t something educators should have to solely take on alone. We all must hold ourselves accountable because, In the end, now is the time and now is a need for us to shift teacher education from focusing on the recruitment of “diverse” faculty members and candidates to the systematic reshaping of policy and the repurposing of resources to authentically support social justice scholars and scholarship, especially when conducted by members of other historically marginalized communities. In doing so all we can hope for and believe is that our efforts to nourish and sustain social justice scholars will be successful.