By: Ariana Rodriguez, Briana Mendoza, Jacob Collantes, and Vanessa Crook

BIOGRAPHY

Dr. Jasmine Phillips Meertins is an assistant professor in the Department of Communications at CSUF, teaching public relations, digital foundations, and event management courses. She holds a Ph.D. in Communication from the University of Miami, an M.A. in International Affairs from The George Washington University, and a B.A. in Political Science from Yale University. She has also taught public relations at Nevada State College and has international experience in higher education administration at Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Miami. Dr. Katherine A. Durante is an assistant professor in the Sociology department at the University of Utah, where she teaches introductory criminal justice courses and sociology classes in crime and inequality. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Cincinnati, M.A. in Sociology from Cleveland State University, and B.A. in Sociology and Criminology from Jon Carrol University. Her research studies focus specifically on racial and ethnic inequality in the criminal legal system and the impacts of incarceration on the family.

Q: What initially drove you to research this specific topic? Did you have a greater intent or goal in mind?

Dr. Phillips stated that her research interests vary and are eclectic but that she typically researches anything regarding interpersonal and intercultural communication. She wanted to work with someone who doesn’t work in the discipline, so when Dr. Durante approached her to work on this study, she was happy to do so. They found a good middle ground that allowed them to research a topic that overlaps with their specialties. Dr. Durante added that as a professor of Sociology, she has always studied incarceration, and one of the facets she focuses on is the impact it has on families, which relies heavily on communication, so she thought it was a well-fit topic for both of them.

Q: It’s clear that quantitative research was conducted for this study. Could you be specific and tell us the steps that were taken to go about it?

Dr. Durante stated that this was a longitudinal study granted by federal grant hours. In some prisons, classes were being taken by incarcerated men on family relationships, all paid for by the federal government. Some of the incarcerated men were taking the class, but others weren’t; in other words, some were getting the treatment, and others were the control group. Dr. Durante informed us that with federally funded programming, some kind of evaluation has to be done, so what occurred is that across five prisons and states, incarcerated individuals with families were recruited and interviewed. After being interviewed, their contact information was gathered, and then an interview with the women was done in community sites where they followed up with them at nine months, 18 months, and some at 34 months.

Q: What do you believe was the main impact of your research?

Dr. Philips stated during our interview that she liked conducting this research because it’s the kind of study that can help change policies. She states that the cost of making jail calls has been a point of discussion recently, as some states have made efforts to make them more accessible. Studies like the one conducted by Dr. Phillips and Dr. Durante can be presented as tangible evidence for policymakers that includes factors such as the cost of phone calls and visitor admission rules, which have an impact on not only the wives of convicts but the rest of the community as well. Dr. Phillips also brought up an interesting point about how this can affect the recidivism of an ex-convict. If a relationship between an incarcerated man and his wife drifts away to the point where it ultimately falls apart, there’s also a chance that his odds of relapsing into crime go up without having a partner to lean upon release.

Q: Were there any obstacles you faced during this study, specifically regarding acquiring data?

Dr. Durante explained that the data used was open source, meaning that anyone can access it. She noted that the average person “off the street” might face barriers getting information and data, but if you were part of an academic institution it wouldn’t be as difficult. She continues to say that the biggest barrier would probably be finding data that exists that can address your research question of choice, because oftentimes it doesn’t exist. Dr. Phillips agreed, stating that the data that they used was collected from 2006-2011, and while it may seem fairly old, it is still relevant because it is the most recent data collected in regards to their research study.

Q: The study expresses that readers should be aware that the study involves only heterosexual couples. Do you believe that there would be any significant differences in the findings had LGBTQ+ couples been included?

Dr. Phillips responded by saying both yes and no. She continues by stating that the main finding of this study is that the longer the incarceration and the more barriers in a relationship, the more likely couples were to say that their relationship became distant and wouldn’t change- regardless of sexuality. She adds that in these particular cases, they also parented a child together, so she wouldn’t know if that would change the dynamic in the case of a same-sex couple. Dr. Durante follows up by stating that the sociological literature suggests that women do most of the maintenance in general, not just with incarcerated families, so she would question that if there were two women, there might be more effort put into overcoming these barriers, but that is just speculation. She continues to say that one of the problems with secondary data is that you can’t control who is in the sample and that there’s just not nearly as much research on LGBTQ+ couples in incarceration.

Q: Why was it so crucial for your study to showcase the effects this has on Black women with incarcerated partners in comparison to other demographics of women?

Dr. Durante conducted the research methods in this study. During her research, she looked at all three groups of women: Black, Latina, and White. Dr. Durante states the most straightforward answer to Black women being the main focus is Black men are far more over-incarcerated than any other group in society. The impacts on families, spouses, and partners disproportionately mean Black women are most impacted by it, which addresses the race decision made in the research. Dr. Durante explains that the most important factor is the fundamental policy implications because it showcases the decisions made by prisons and jails, typically state institutions. Knowing how vital family relationships are to a successful reentry to society, these institutions cast policies that are harmful, making the reentry process to society more difficult for past incarcerated men.

Q: Did the results from the Likert scale survey produce the results you expected?

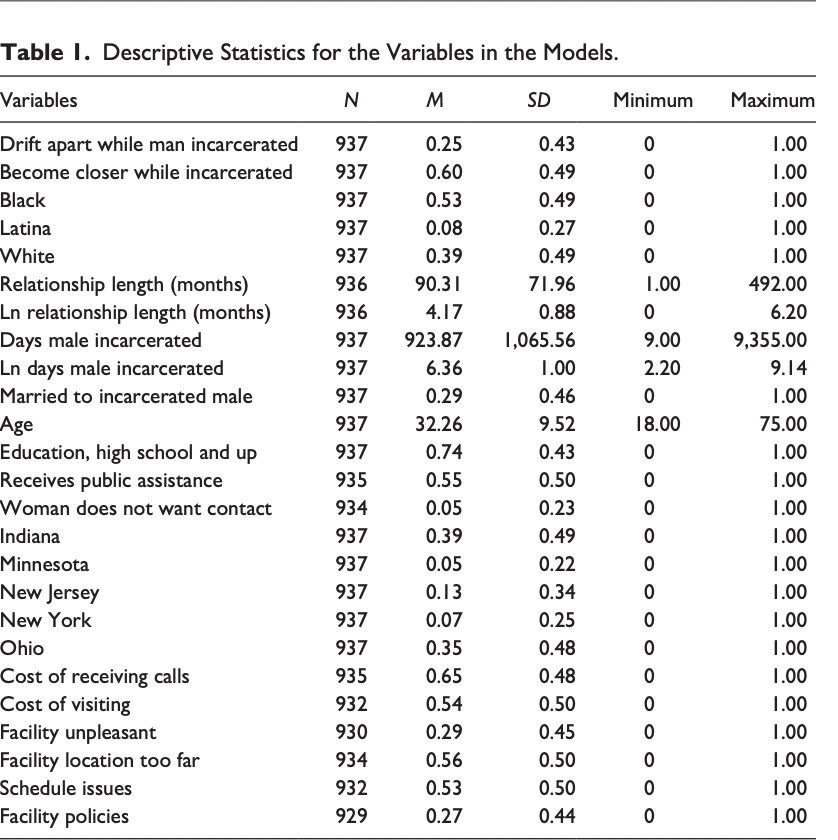

The experiment was conducted using a Likert Scale survey. The first question asked was if the incarceration of their husbands changed their relationship with each other. A four-point scale was used where one meant strongly agree, and four meant strongly disagree. After that, the questions turned into two-point scales, in which the responses were either Agree or Disagree. The objective of these two-point questions was to see if things such as the distance of the prison, visitor admission rules, the cost of visitation, the association of seeing their husbands in prison, and scheduling conflicts were factors that prevented these women from seeing their husbands, therefore affecting their relationships. Dr. Durante stated during our interview that, for the most part, the hypotheses showed a direct correlation to women feeling like their relationships with their incarcerated husbands were drifting apart. However, the one exception to this was that the cost of the visitation was not as significant of a factor as anticipated. Instead, the cost of phone calls was seen as a much more significant barrier. There was no correlation between the cost of visitation and relationship conditions.

Q: If you can do this study again, would you change it, or leave everything as is?

Dr. Durante explains how she knows the data well, so she has many opinions, but if she had the chance, she would add more control variables, and since she has played with the data enough she doesn’t believe it would change the results but for strengthening the presentation results it would be great to add more variables to the model.

Q: As conductors of the study, do you feel there has been improvement in finding alternatives within judges and legislature to imprisonment now or in the future?

Dr. Durante believes there has been no improvement within judges and legislature finding alternatives, and there won’t be anytime soon. In 1980, the United States started mass incarceration, and incarceration rates were growing until 2010, this happened despite crime rates from 1995 to 1996 plummeting. Crime today has plummeted but the public is not aware of this, most Americans believe that crime has increased because the media has influence on all of us. People tend to go towards the media instead of checking data. In 2010, multiple states realized they were spending money on incarcerated people, and it hadn’t been helping with public safety. Multiple states started to purposely address laws that would re-appeal some tough crime bills from the 1990s, which resulted in the effectiveness of incarceration trends. Data shows that, from 2010 to 2020, incarceration finally started to decline because of state laws. In 2022, those ten years were reversed, and incarceration rates went up once again. Dr. Durante believes in the heated political divide and rhetoric and how there is a big push towards retribution and tough-on-crime policies again. In our group, Ariana Rodriguez mentioned a connection between this research topic and the prior 2024 election, in which one of the propositions was about incarcerated people.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Dr. Phillips and Dr. Durante’s research allowed us to enhance our understanding of perceptions of relationship quality among women with incarcerated partners. The impact of having an incarcerated significant others is associated with negative impacts which brings barriers for the whole family which is represented through Black women in this research study. Prison-related barriers include expensive phone calls and difficulty with in-person visitations. These are the primary sources of communication and without their presence, they result in distance and separation of connections within relationships.